Dance and Play with Tantsulaul by Veljo Tormis

Last year, our Tenor/Bass choir sang in Estonian for the first time and (some of them) loved the language so much they requested more! Enter Tantsulaul by Veljo Tormis: an upbeat dance song telling the story of a not-so-good dancer who thinks he is just the best. Take a listen to the Svanholm Singers perform Tantsulaul here then get to know the piece below through the following:

- Featured Composer: Veljo Tormis

- Estonian Choral Music

- The Story of Tantsulaul

- Estonian Dances

- Tantsulaul Teacher Resources

- …and so much more!

Sing and Dance with Tantsulaul

When planning a concert set, I always like to have one short and sweet, easy-to-learn, and maybe a little bit silly piece. For our “Singing our Roots” concert this fall, Tantsulaul is that selection for the tenor/bass choir. Telling the story of a man who loves dancing, but can’t quite deliver with his dancing moves, and connecting to eastern European roots, this piece allows singers a chance to loosen up and have some silly fun.

Tantsulaul is the final of eight songs in Tormis’s song cycle Meestelaulud (Men’s Songs) with texts edited by Estonian poet, playwright, translator, and politician Paul-Eerik Rummo. Many of the tunes and texts in this piece are traditional, brought back by sailors from trips abroad and sung only in the presence of men due to the sometimes risqué subject matter.

Luckily, singing about dancing is no longer risqué, so the piece is an excellent piece for any tenor/bass choir. Although the piece is in four-part harmony, the harmonies are very digestible and quick to learn. Although the Estonian language can be a challenge, you can find an IPA translation on the publisher website here.

Featured Composer: Veljo Tormis

Born in Kuusalu, Estonia in 1930, composer Veljo Tormis is known for his championing of Estonian folksongs and stories. With over 500 individual choral songs to his name, Tormis loved sharing music that shared something about the world, nature, or people.

Born into a musical family, Tormis found his choral foundation as he sang in his church choir. When he began composing, he found himself interested in utilizing a national style based on the use of folk music. Over time, he transitioned to using rustic and often archaic folk materials in their original manner and building choral works around the tune. Tormis enjoyed using materials from pre-Christian and medieval times from Finland and Estonia, and often relied on the anceint form of Estonian folksong called regilaul.

Text and story were very important to the composer. Contrary to the desires of many composers, at times Tormis would encourage foreign choirs singing his works to translate the words to their own language. Although he knew some of the poetic nuances would be lost in translation, he wanted audiences and singers to understand what was going on story-wise throughout his works.

The parallels between Tormis’s life and the history of Eastern Europe as well as the international development of choral music is quite interesting. For further reading, I encourage you to check out the composer’s biography on his website linked here.

Estonian Choral Music

Tantsulaul has been classified as a transitional Estonian folksong. During the nineteenth century, transitional folksongs like Tantsulaul began to replace ancient runic singing traditions from the region.

The Estonian Folk music tradition was first mentioned in 1179. Older Estonian folk songs are also called runic songs and were popular until the 18th century. At this time, more rhythmic folk songs (like Tantsulaul) became more popular.

Traditional instruments were used to accompany folk tunes or play dance music. These include shepherd instruments like the karjapasun (shepherd’s horn or trombone) and the vilepill (whistle with a mouthpiece and finger hoes), and other instruments such as the torupill (bagpipes), fiddle, zither, concertina, and accordian.

Choral music is strongly connected to the history, culture, and politics of Estonia. The first Estonian song celebration was observed in 1869, and has continued to today. The Tallinn Song Festival Grounds was built in 1960 and hosts tens of thousands of singers and attendees every four years.

Song and choral festivals became even more popular in the 20th century as a sign of nationalism and independence. In 1988, Estonians joined together to begin with other Baltic States in what has been titled “The Singing Revolution.” Through spontaneous mass evening singing demonstrations at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds over several years, Estonia gained its independence in 1991 without blood shed.

Story Time: Meaning of Tantsulaul

According to the composer, Tantsulaul is a humorous account from a man who fancies himself a good dancer. The first verse translates to “Let our Mari come, I shall get her on her feet.” The dancer is convinced that he is so good, he will be able to get the reluctant dancer, Mari, enjoying herself on the dance floor.

According to the octavo, the second verse says “My sock heels have holes like an old mare’s blaze.” A blaze is thick vertical white line down the face of a horse – in this case, a female horse. Although, google translate says it’s actually “old mare’s eyelids.” Any Estonian speakers out there who can confirm or deny? Either way, the dancer has danced so much that he has worn substantial holes in his socks.

The final verse reads “My ears are singing as if Jüri from next door was playing the pipes.” In this case, perhaps the music is quite loud and his ears are ringing like they might after hearing bagpipes played nearby.

The refrain “Ait-tali-rali-raa, ali-ramp-tamp-taa. Utireetu, utireetu, trallallaa” has no translation, and is likely imitating dance instruments like the shepherds horn and whistle played above or imitating the sound of certain dance steps.

Clapping, stomping, whistles, tongue clicks, and other sounds and actions add to the interpretation of the lyrics as you listen to the piece. What do you think – did our protagonist get Mari dancing?

Estonian Dances

The hero of Tantsulaul is quite sure of his ability to dance, and get others dancing. Due to his love of folksong and culture, composer Viljo Tormis’s work has helped to preserve and uplift Estonian National Music and Dance. Prior to the 1850s, Estonian dance had begun to reflect Russian culture, with polkas and waltzes and quadrilles.

In the mid-19th century, Estonian associations were founded in order to awaken national spirit. During this time, ethnographers visited all corners of Estonia, collecting folk dances from (generally elderly) folks. They found that Estonian folk dance is characterized by collective, simple, repetitive movements presented in a peaceful and dignified manner. Line dances and circle dances were common with very little extraneous movement.

As is the case with much folk music, the same dance may be performed differently from town to town as the people of different regions adapted to their own needs and likes. In recent years, dance clubs have formed to learn old dane patterns and folk dance groups continue to compete in conjunction with the Estonian Song Festival. For an idea of the variety of Estonian folk dances, take a look at the Märt Ago Estonian Dance Troup’s performance at the Kennedy Center linked here.

Complementary Pieces

Want to listen to other pieces like Tantsulaul? Or planning a concert and need some programming ideas? Here are a few complementary pieces!

Loving the Estonian Choral Music vibe?

- Muusika by Part Uusberg for SSAA and SATB is a gorgeous tone poem that had my singers obsessed.

- lus Haal by Margrit Kits and arranged by Laura Jekabson for SSAATB is just so cool. Written in honor of Estonia’s 100th anniversary, the piece features Latvian lyrics and percussive elements.

- Estonian composer Eriks Esenvalds has a wealth of choral compositions. My most recent obsessions include The Sea Wind with handbells and Stars with six tuned water glasses. Both feature text by Sara Teasdale and are SSAATTBB arrangements.

Here are a few of the other folk “roots” themed pieces I’m pairing with Tantsulaul this concert cycle for our tenor/bass ensemble:

- Martin Schröder’s Randy Dandy O

- Susan Labarr’s The River

- Michael McGlynn’s Fionnghuala

- The full “Singing Our Roots” program round-up

I’d Love to Hear from You!

Have you sung or conducted Tantsulaul with your choir? What story did you and your choir portray? Did you connect the piece to any specific dances? Do you have any other favorite Estonian choral pieces? Let me know in the comments section below!

Tantsulaul Teacher Resources

Free Comprehension Worksheets

Choir Leaders! I have begun to include short comprehension worksheets with each Inspired Choir blog post. Each worksheet includes 5-6 knowledge-based questions about the post and concludes with a musical decisions/applications question. Use as a homework assignment, sub activity, listening challenge, or guide for conversation in class. Fill in the form below to receive a link immediately to all “Roots” Worksheets.

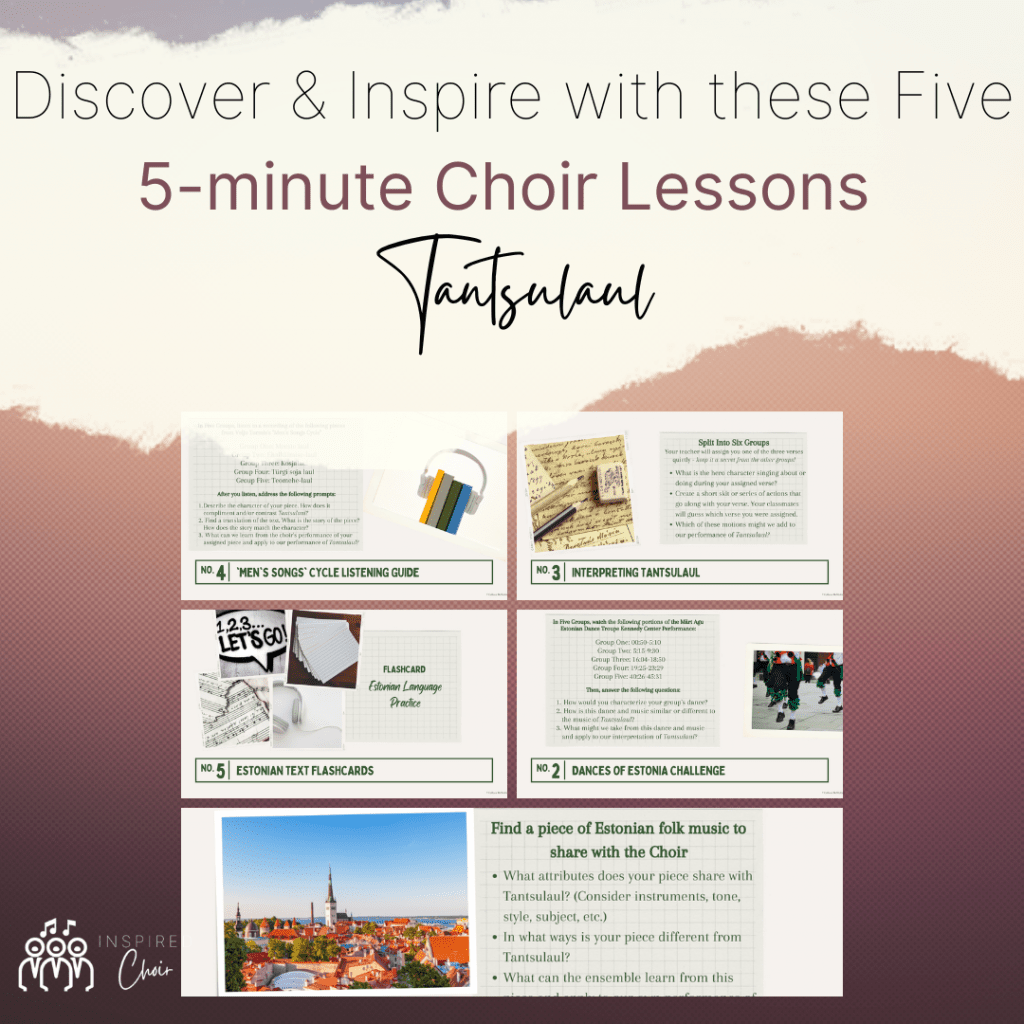

Tantsulaul Lesson Plan Bundle

Check out the Inspired Choir Shop for the Tantsulaul Lesson Plan Bundle. This bundle includes the following five minute lesson plans, all with connections to National Standards and SEL Competencies:

- Estonian Music Exploration

- Dances of Estonia Challenge

- Text Interpretation Activity

- Men’s Songs Cycle Listening Guide

- Estonian Text Flashcards

Singing in A Different Language Worksheet

Check out the Inspired Choir Shop for the Singing in A Different Language Worksheet. Utilizing this worksheet, singers will:

- Examine the characteristics of the language in which they are singing

- Consider the ways in which the composer has highlighted the language in their work

- Anticipate challenges of singing in the language

- Interpret the meaning of their piece

- Prepare their score with the appropriate annotations